(i) As for me, the relevant facts are undoubtedly buried somewhere in my past, and relations with family history somehow. I don't have much inclination to do the digging itself right now, and unless there's a little bit wrong with you, neither do you. (Chase down the link, if what's wrong is that you're a shrink of some kind). Let's drop it.

(ii) I've got only the fewest unargued words to say about collecting generally. I am sometimes told that collecting is silly, and sometimes even that it's not a good thing to pursue. I suspect that everyone should collect something -- and it may well be that almost everyone does. If at some expense you have sought to acquire (own) five of some kind of thing F that you want too keep because they're Fs, don't thereafter have a moral obligation to keep, don't need, and would be happy to acquire and keep more because they're Fs, then you collect Fs. Depending upon the value of F, five can represent either a humble collection or a serious one. Five antique cars is serious; five vases isn't really very serious, unless they're old Dresden or rare Rookwood or the like. Why should everyone collect something or other? As I say, my few words are unargued. (The reader will notice that my sufficient condition above puts few restrictions on permissible values of F. If you find yourself disliking the idea that you should collect something, take heart in the fact that you probably do collect something, and it'll feel better. Genealogists have, at some expense, acquired beliefs of a kind they want, don't have a moral obligation to keep, don't need, and would be happy to expand. So have philosophers. Collectors needn't acquire material things, and if material things of kind F don't contribute to their overall happiness in any way, then they probably shouldn't collect them. In general, to be happy is to have around you the kinds of things that increase your happiness; and since happiness is a virtue, folks should, other things equal, strive to have those kinds things around them. The ceteris peribus clause saves us from a multitude of sins. I shouldn't be taken for claiming that all values of F are equally valuable collectibles; so I shouldn't be understood as claiming that for any collection C, the person S whose collection is C is better off for having C. [If S is a bad person, S will probably collect bad things -- maybe some good things too, but that's neither here nor there at the moment.] But hey, look: I said I wasn't going to argue for things, so let's quit this.)

(iii) About old stuff, I also have only the fewest things to say. Folks who know their place in the world know their temporal place in the world. To know your temporal place in the world isn't simply to know just any old bunch of before-after propositions; it's to know temporal facts about the world that figure importantly in the beliefs you have, and should have, about what you find valuable in your life. (Here, as above, what one values might be have little or no value. As above, that is neither here nor there at the moment.) In particular, folks who know their temporal place in the world know two things: (1) First, they know that they're beholden to others -- most of whom came before, from whom they have inherited innumerable kinds of goods. One cannot properly appreciate those to whom one is beholden, nor the goods they bequeathed, in sheer ignorance of them. And one should properly appreciate them. (2) Second, they know that making sound judgments about value and goodness can't be done well in a vacuum. In Part I of the Discourse on Method, Rene Descartes writes that "Conversing with those of past centuries is much the same as travelling. It is good to know something of the customs of various peoples, so that we may judge our own more soundly...." That's right, applied to various parameters of value generally.

Meanwhile, there is nothing wrong with finding the past instrinsically interesting, in its own right, as it were. Why we find interesting the things we do is another question (or questions, as we'll see). But justifying interests is sometimes much like justifying likes and dislikes when it comes to food: if you enjoy the flavor of something, there's scarcely more you can say about why you do. 'Why' here doesn't express the request for a genetic account (of how you come to have the sort of palate you do), but the request for a justificatory account (of what warrants or licenses your having the sort of palate you do). And the point is that there is no warrant or license for liking this or that food. You just do, and requests for justification are rather misplaced. Some people find historical facts and objects interesting in the way they find certain foods (but not others) pleasant. Well, good enough, then. I'm like that. I find old stuff intrinsically interesting. There is doubtless some genetic story to be told about the provenance of this, but all of that was set well enough aside in (i) above.

(iv) Tools themselves? Well, perhaps here too there's little more to be said about my interest in them than there is to be said about my liking good beer. If much more is sought, the more would likely trickle back up to issues set aside in (i) and given a lick-and-a-promise in (iii). In the former case, I came from a poor family that used tools, so as a bit of autobiography, we needed and were taught to appreciate them, and old ruts don't fill in very readily if they're worn in the right way. On the latter score of historical concern, tools themselves -- the objects, I mean -- really do serve as a splendid snapshot of the craftsmen who used them and the innovators who fashioned them, very often with great care and pride and cleverness. In reflecting efforts to accomplish what cannot be (or cannot readily be, or cannot be well-) accomplished without them, tools tell us something about what is, or has been, judged to be of value. They make our lives easier, better.

Philosophers will find this tiresome. Is there any philosophy

nearby? I don't much care about that. (But you can find it

if you want to find it. Two examples, maybe three. (1) The

first comes -- thankfully, as you'll see -- from Spinoza, and epistemic

issues, or "the problem of the criterion" as Chisholm called it.

In his Tractatus de Intellectus Emmendatione, Spinoza considers

the infinite regress threatening anyone who requires some criterion or

method by which to justify appropriating some epistemic criterion by which

to justify.... By Spinoza's reckoning, "to find the best Method

of seeking the truth, there is no need of another Method to seek the Method

of seeking the truth, or of a third Method to seek the second, and so on,

to infinity. For in that way we would never arrive at knowledge of

the truth, or indeed any knowledge" (Gerhardt II/19-22). His analogy,

perhaps owing to Bacon, is this: "For to forge iron a hammer is needed;

and to have a hammer, it must be made; for this another hammer, and other

tools, are needed; and to have these tools too, other tools will be needed,

and so on to infinity; in this way someone might try, in vain, to prove

that men have no power of forging iron." Spinoza reckons that

we begin with tools we're born with, already to hand. The hand comes

to mind, near to hand as it always is, as does the mind itself. The

skeptic can go play darts, or billiards with Hume. (2) Second --

if a bit of a strain -- comes from Thomas Jefferson, and ethics.

Folks who make tools use them, as Spinoza just taught us. Jefferson

suspected that folks who used tools might well be those to whom one should

look for the most sound counsel. Or anyway, plowmen were as ethically

good and smart as the next fellow, and perhaps better and smarter.

In a letter to Peter Carr of August 1787, Jefferson wrote: "State

a moral case to a ploughman & a professor. The farmer will decide

it as well, & often better than the latter...." It is a disputed

point of Jefferson scholarship whether he indeed had systematic proposals

about pragmatic foundations for education reform; but there we are.

I tend to think that carpenters and farmers and smithys are...wiser

than most folks. (3) Finally -- alas -- we have Heidegger,

in the Phenomenological Interpretation of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason.

Never mind the transition from a prescientific comportment to the scientific

comportment by the basic act of Objectification: it's unintelligible rubbish,

of course. But he saw clearly enough that one can't get much smarter

about the concept Tool itself by using a particular hammer or axe,

and that it is by a prior grasp of Tool and knowledge of some object

as an instance of it that we get smarter about what hammers and axes do

for us. "We do not develop this understanding [of Tool, say] in the

course of use. On the contrary, we must already understand ahead

of time something like Tool and Tool-character, in order to set about using

a certain tool...What we learn is not an understanding of what being a

tool is in general, but rather we can only learn the use of a specific

tool as we anticipate and ask for it" (Section 2: Laying the Foundation

of a Science). There you go, if you want philosophy. For my

part, the philosophy tends to be distracting when it comes to tools --

especially old ones.)

AXES

So Elisha went with them. And when they came to the Jordan, they cut down wood. But as one was felling a beam, the axe head fell into the water: and he cried and said "Alas, Master!" -- for it was borrowed. And the man of God said, "Where fell it?" And he shewed him the place. And Elisha cut down a stick, and cast in in thither; and the iron did swim.-- II Kings 6:5-6, King James Translation

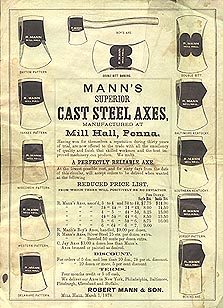

The famous "Lincoln Axe" and the Kelly "Perfect Axe" and the "Black

Raven" mark (also of Kelly) are fine examples of this genre of tool, boasting

their quality and warrantee in plain terms on the face of the axe, warning

of imitations, and often accompanied by an elaborate script or likeness

of an indian or a woodchopper or famous historical figure (or, a black

raven). If you find one in good shape, you're two or four hundred

dollars better off.

Sometimes, embossed hatchets were used for purely promotional purposes, advertizing shoes or coffee and given as a premium to buyers of such products. Poll Parrot shoes gave away hatchets, as did Buster Brown Shoes. And so did the good folks at Canova Coffee...

Why are these embossed axes and hatchets rare? Well, the practice didn't last all that long: as the composition of axe steel came to be increasingly hard, this process became increasingly impractical and cost-ineffective. And early in the 1940s, many axes were melted down in the iron drives for the war effort. Of the old axes that survived, many went the way of all things here below, where (moth and) rust doth corrupt. Good embossed axes are hard to find. They are aesthetically pleasing, typically of very high quality, and capture something of an era of tool manufacturing and use when the pride of workmanship was well-earned and worth announcing. They don't make them like that any more.

They didn't make them like that before the late 1800s either.

Before then, they were largely the product of individual blacksmiths, not

large manufactories. Collectors of axes are invariably excited to

see a smith's mark ("touchmark") on an old axe, sometimes even a name,

and several industrious souls have gone to considerable scholarly lengths

to uncover the history of individual axemakers. Rarity runs along

other parameters too. Some styles of axe were in far less demand

than a typical felling axe. There were fewer coopers (cask-makers)

than run-of-the-mill woodsmen and country folk, so there are fewer coopers

axes to be found than felling axes. The Kent-style mast axe, used

in the bridge-building industry, is even more rare. There are axes

of more kinds than you might think: boarding axes, which Mr. G.P.B

Naish of the National Maritime Museum says were "carried by boarders and

used to damage the enemy's ship, cut up its rigging, hack through a spar

and smach through a bulkhead...;" broad axes, used for squaring structural

timbers or rail keepers; butchers axes, for slaughtering, with a poll on

the head to stun the animal first; coopers axes, with a squared thin edge

beveled on just one side with a cantered handle (to save one's knuckles),

for listing barrel staves; cricket bat-makers axes, with a wide curved

symmetrical blade for shaping willow blanks into cricket bats; felling

axes, of at least twenty different styles; fireman's axes, with a pick

poll and strapped handle; hedging axes, for cutting when laying a hedge;

morticing axes, with long narrow blades for cutting a mortice to receive

a tenon; turpentine axes, for starting a proper run of sap; and on and

on.

You may find this boring. You may find old tools

boring. There are, indeed, boring tools....

BORING TOOLS

...for boring holes, of course. You see a sample of one such kind above -- the hand auger, outfited with cutting edges of varying sorts. The cooper used a bung borer, slightly tapered, and then he might use a bung bushing auger to complete the task. The shipbuilder and bridgebuilder used long raft augers to make way for long wooden pins in big ship timbers; the barnbuilder did something similar. The auger bits themselves might be of a Russell Jennings pattern, or a solid-center Irwin pattern, or a single-twist (L'Hommedieu) pattern. Miniature augers -- gimlets, not illustrated above -- were used by bell hangers (to allow for passage of strings for pulling bells), brewers (for vent holes in shives of barrels), shipbuilders (for smaller rivet-spikes), and so on. Large open augers were used by wheelwrights, in fashioning the hub. The common brace-and-bit, familiar from your dad's shop, was of course a mainstay for woodworkers of all sorts. And, again, on and on. They aren't boring, these boring tools: they're fascinating.

PLANES

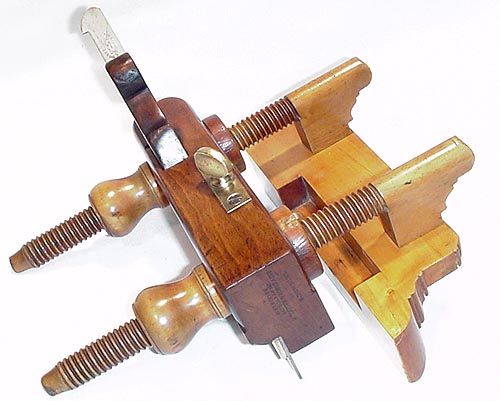

Planes come in all shapes and sizes, designed explicitly for more purposes than you might at first imagine. Rhykenologists study them, in long written treatises -- their kinds (plow plane, molding plane, rabbet plane, fillester plane), their uses (sashmakers, joiners, furnituremakers, coachmakers, coopers, violin makers, shipbuilders, bridgebuilders, finish carpenters, and on and on), their molding profiles (grecian ogee and bead, astragal, scotia-bead with cove, double side reed, center fluting, snipe bill, and hundreds more), their manufacture (by hand, alone; with an apprentice; by prison labor with water power; in a small team by horse and dog [yes! -- see below] power in a villiage, or by steam power in the city), their methods of adjustment (wedge arm, two-arm screw, three arm center screw, etc.), what sort of wood they're made of (yellow birch, beech, lignum vitae, live oak, rosewood, some of one or two or three of these), and on and on. It's all fascinating business, about which scholars -- that's right: scholars -- continue to learn, and examples of which collectors pursue with all the fierce single-minded pathology you can imagine....

[Still working...]