GENERAL TRENDS OF THE EARLY 4TH

CENTURY BC: THE DECLINE OF THE GREEK POLIS

Download Greek Map Set

Click Here for the following

images: Alcibiades, Leuctra

Monument, Messenian Gate

Broader Trends in

Greek history: Particularism vs. Panhellenism

Particularism: Identity with

one’s local community (polis) vs. identity with Greece as a whole

Panhellenism: Recognition of wider Greek common cultural

attributes (language, religion, gymnastic educational system)

Persian Wars

499-478 BC – The Hellenic League (Sparta was hegemon – commander in chief of allied military

campaign), the city states of Greece

banded together to resist the threat of conquest by Xerxes I, King of Persia.

Persian expedition was defeated on sea at the Battle

of Salamis (480) and on land at the Battle of Plataea

(479). Spartan unwillingness to lead a crusade to liberate the rest of the

Greek world from Persian Domination led to the formation of the Delian League (478 BC), with Athens

as hegemon, but still member of Sparta’s

Hellenic League. Overlapping jurisdictions inevitably led to tension. Delian League was a joint voluntary military alliance in

which each state contributed military contributions (phoros)

according to its means.

Congress Decree 448 BC, Pericles announced

that the Delian League must continue, as well as its phoros (cash contributions) despite cessation of hostilities

with Persia.

At this point the Delian League became an Athenian

Empire. See External

Conflict in the Greek World lecture for Athenian Tribute Lists

Peloponnesian War

431-404 BC – Sparta

and its allies called on the subject states of Athens

to rise up and join the liberation of the Greek world from the tyranny of Athens.

Alcibiades of Athens

Athens and Delian League v. Sparta and the Peloponnesian League (Sparta

Argos, Corinth, Thebes). First half of

the war (431-421 BC, Archidamian War) ended in a draw

with the Peace of Nicias obtaining the “status quo” for 6 years. In 415 BC, the

Athenian leader, Alcibiades (ward of Pericles, student of Socrates) convinced

the democracy to attempt to conquer Syracuse in Sicily. He was soon

indicted for sacrilege prior to the departure of the fleet but he escaped and

fled to Sparta where he was welcome as a guest friend of the Spartan king and

advised the Spartans to defeat Athens: 1. by assisting with the defense of

Syracuse, 2. by invading Attica and remaining there throughout the year (Decelean War, 415-404 BC), and 3, by dispatching an embassy

to the Persian King to demand financial assistance with which to build a fleet

to compete with Athens at sea. This brought success including the annihilation

of the Athenian expeditionary force at Syracuse (412 BC); however, Alcibiades’

affair with the queen of Sparta in her husband’s absence led again to flight,

this time to the palace of the Persian satrap (governor)_in Sardis (Lydia).

Again, he wisely advised the Persians to support both Sparta

and Athens to wear both parties down so that Persia could

benefit from their mutual destruction. His support of Athens led to his recall (409) and

exoneration from past charges. He actually led the Athenian naval retaliation

vs. Sparta in

the waning years of the war. However, the resurgence of Athens

and reorganization of the Persian hierarchy in the Aegean

(King Artaxerxes II send his brother Cyrus II to

assume command of Persian interests in the region), resulted in a renewed

understanding between Cyrus and the Spartan general Lysander. A secret deal was

struck by which Cyrus would fund Lysander at sea and defeat Athens;

in exchange, the Spartans would cede all previous Persian possessions in the

region (the cities of Ionia) back to Persia. Mismanagement of the

Athenian navy soon led to Alcibiades further indictment, flight and abandonment

of the Athenian cause. He was later killed by the Persian satrap of Bithynia on

Cyrus’ orders. The Spartan-Persian alliance ultimately led to Lysander’s defeat

of the last remaining Athenian fleet at the Battle

of Aegospotami (404 BC), the naval blockade and siege of Athens and Athenian surrender (401). A

pro-Spartan hierarchy was imposed on Athens (the

30 tyrants, led by Socrates’ student Critias) who

purged hundreds of leaders of the democracy, and the Long Walls that defended

the Piraeus

were brought down.

Early Fourth

Century Politics in Greece: Greek

warfare continued unabated following the Peloponnesian War. As destructive as the Peloponnesian War proved, the

level of violence in Greece

continued to rise in the following era. Conflict remained incessant during the

fourth century as city states continued to realign themselves into shifting

alliances in order to combat the threatening military ascendancy first of

Sparta (404-371), then Thebes (371-362), and then Athens (362-357). The

bewildering rotation of alliances appears to reflect the innate tendency of

Greek city-states to restore particularism, city-state autonomy, by weakening whatever power

appeared to be on the verge of asserting political ascendancy over others. The

result was to leave the Greek mainland divided and resentful of one another at

the very moment that outside powers were again threatening to exert their

influence over Greece

as a whole.

Era of Spartan

Hegemony, 401-371 BC – Sparta

attempted to assume control of the member states of the Athenian Empire

following the defeat of Athens

in 404-401 BC. It had secretly colluded with Persia

to raise the money to defeat Athens

at sea. It had agreed to surrender the Greek states of Ionia to Persia in

exchange. Sparta’s allies became alarmed at the

growing ascendancy of Sparta

and mounted a conflict against it.

(Alliance structure at this

time: Sparta vs. Corinth, Argos, Thebes, and Athens)

King Agesilaus of

Sparta, a great king who nonetheless witnessed the dismantling of the Spartan

hegemony on his watch

– growing evidence of manpower shortages in Sparta (for the

Spartan hoplite aristocracy, see Archaic

Greece and the Rise of Tyranny.

Xenophon, the March of the

10000, and Cyrus II – 401-399 BC. Cyrus II, brother to Persian King Artaxerxes II and favorite son of the dowager queen, was

assigned to the Persian command of the Aegean as military satrap to resolve Persia’s role

in the Peloponnesian War. He forged an alliance with the Spartan “admiral”

Lysander that successfully brought Athens

to surrender. His ulterior motive was to recruit Greek mercenary support for

his bid to overthrow his brother as king. Some 10,000 Greek mercenaries, many

of them exiles, joined his expedition, including Xenophon, an Athenian

aristocrat and student of Socrates. At the Battle

of Cunaxa outside Babylon,

Cyrus and his combined Persian-Greek force defeated the arm of his brother on

the battlefield. He himself was killed, leaving the Greek contingent stranded, deep

in Persian territory. Devoid of its leader Cyrus and soon deprived of its Greek

mercenary generals, this Greek army marched over a 1-year period and fought its

way out of “Persia” by heading north to the Black Sea. Most of the warriors

successfully made their way back to Greek territory, Byzantium, by which time Artaxerxes

and the Spartans were at war, led by King Agesilaus.

Xenophon reports that many of the survivors reenlisted for this new conflict.

This expedition demonstrated the inferior state of readiness of the Persian

military establishment, vis-à-vis Greek hoplite warfare, and inspired many

military and political thinkers in Greece

to conceive of the day when Greek armies would conquer Persia.

Spartan weakness, the helot

situation in Messenia (see Archaic

Greece and the Rise of Tyranny). Messenia – helots – serfs, Messenian (Greek)

farmers tied to the land to support the families of Spartan full-blooded

hoplite warriors and their families. The presence of this suppressed population

limited the range of Spartan military ventures. The Spartan Council of Elders (Gerousia) never wanted the army too far from the Peloponnesus in the event of a helot uprising.

Peace of Antalcidas

387 – Brought the temporary end to hostilities following the Corinthian War (Sparta vs. Greece).

The Peace was imposed by the Persian King Artaxerxes

II and “enforced” by King Agesilaus of Sparta. It lasted

briefly.

Boeotian League of Thebes – Thebes became hegemon to a

military empire based on its native region of Boeotia.

Ignored by Greece since the

Persian Wars, Thebes had avoided participation

in the Peloponnesian Wars and had grown in population and power in its home

region of Boeotia at the end of the Fifth

Century BC. It was still vulnerable to Spartan assault, but its leadership was

determined to establish the city state as a leading force in Greece.

Seizure of the Cadmeia 382 BC – Spartan army seized the acropolis of Thebes and imposed a

garrison. This insult led to the emergence of generals Epaminondas and

Pelopidas in Thebes.

Hatred of Sparta

led to the expulsion of the Spartan garrison by Theban patriots led by young

Pelopidas (378 BC), soon to be commander of the Theban Sacred Band in 378. The

Theban Sacred Band was an elite force of 600

young aristocrats sworn to sacrifice themselves for the good of Thebes. Rushing out ahead

of the Theban oblique phalanx at the Battle of Leuctra, the Sacred Band caught the Spartan right flank

in lateral motion and broke the line of the Peloponnesian League Army.

Homosexual relationships among their ranks bonded the warriors of the Sacred

Band emotionally as well as patriotically.

Era of Theban

Hegemony 371-362 BC – By defeating Sparta

at the Battle of Leuctra, Thebes assumed the hegemony of combined Greek forces

(these at first included Athens, Corinth, and Argos) to weaken Sparta both in

the Aegean but most particularly in the Peloponnesus, where repeated invasions

by Epaminondas led to the dismantling of Sparta’s Peloponnesian League.

Epaminondas successfully liberated Messenia and the helots and created the

fortified settlement of Messene.

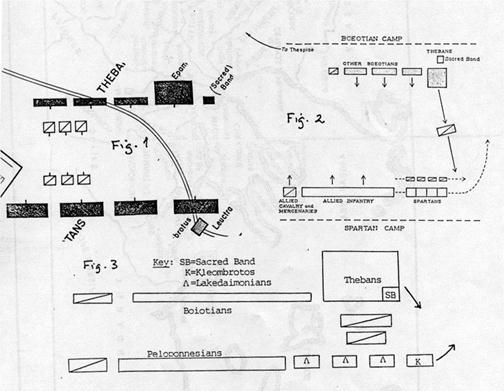

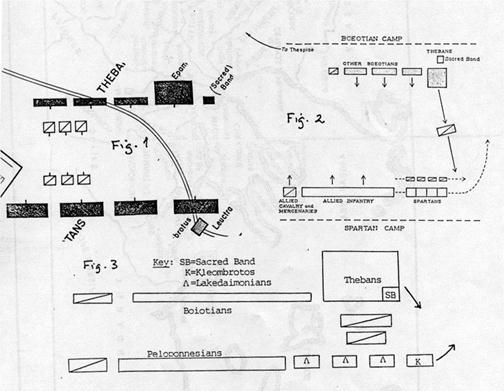

Battle of Leuctra Diagrams Showing Use of the Oblique

Phalanx by Placing Deep Ranks of Theban Hoplites on the Left Flank to Attack

the Exposed Right Flank of the Spartan Army.

Victory Monument erected by Epaminondas of

Thebes at Leuctra

Battle of Leuctra 371 – Using

the Oblique Phalanx and ‘Joint Force Operations’

of cavalry, peltasts, slingers and archers, the

Theban generals Epaminondas and Pelopidas outmaneuvered the Spartans on the

battlefield and decimated the Spartan hoplite army. The Spartan army suffered

an irreversible setback (loss of elite troops), and Spartan hegemony over the

Peloponnesian league was undone. Sparta was

suddenly exposed to repeated (4) invasions of Laconia

by Thebes,

supported by many former Peloponnesian League allies. Epaminondas liberated

states such as Messenia and Mantinea

from Spartan domination and helped to construct urban defenses.

Megalopolitan Gate at Messene

While Epaminondas dismantled

the Spartan hegemony in the Peloponnesus, Pelopidas exerted Theban hegemony to

the north, to Thessaly and Macedonia.

During one expedition, ca 368 BC, Pelopidas took the Macedonian prince, Philip

II, hostage as leverage toward the good behavior by his older brother Perdiccas, the king. As a teenager Philip observed and

participated in Theban military operations and learned the advantages of “joint

force operations” and the “oblique phalanx”. Pelopidas died soon afterward in a

campaign in the Thessaly (Battle of Cynoscephalae 364 BC).

Battle of Mantinea 362 –

Epaminondas again relied on the tactical flexibility of the oblique phalanx to

outmaneuver Sparta, Mantinea, and Athens outside

the walls of the Peloponnesian state of Mantinea.

Though victorious on the field, Epaminondas was wounded in battle and died at

the moment of victory on the field. This followed Pelopidas’ demise in northern

Greece

2 years earlier. For all their success and brilliance, Epaminondas and

Pelopidas had no successors capable of sustaining the Theban military

supremacy. Thebes reigned in its influence and

interests to the immediate vicinity of Boeotia.

(Alliance structure at this

time: Thebes vs. Sparta, Athens, Corinth)

2nd

Athenian Naval Confederacy 378 – 357

(Social War) – While all this was going on, Athenians had been attempting to

reconstitute the Delian League alliance of the 5th

century BC, without resorting to tribute collections. Without guaranteed funds

the alliance was doomed. When Athens

finally attempted to impose force contributions, the allies rebelled (Social

War, 357 BC) and the alliance collapsed. The Social War 357 BC, demonstrated

the inherent weakness of the Athenian naval position: the financial

impossibilities of the confederacy and the collapse of Athenian naval power.

Emerging Trends of

4th Century BC Greek warfare:

Ø MERCENARIES - Xenophon, March of the 10000 (Anabasis) 401-399 BC; Evolving

professionalism of hoplite tactics: Oblique phalanx, Epaminondas and Pelopidas

of Thebes, Battle of Leuctra 371 BC Professional skirmishers – peltasts, slingers, archers; large cavalry formation used

as an offensive weapon; Coordination of complementary units on the battlefield:

‘Joint Force Operations’

Ø 2. Individualism

– disengagement (disenchantment) of elite members of society from their

respective city states. A growing tendency to see themselves as men of the

world, not the polis.

Ø 3. Political

Apathy – withdrawal from political life at the local level; Example: Athenian

liturgies – voluntary philanthropy, from wealthy individuals maintaining

triremes during the 5th century BC to avoidance of such

responsibilities during the 4th.

Ø 4. DECLINE IN THE IMPORTANCE OF THE POLIS – emerging

elements of mercenaries, financiers and dignitaries who saw themselves as

existing in a world that transcended the polis.