Arrian

1.13-15; Plut. 16; Diod. 17.19.1-3

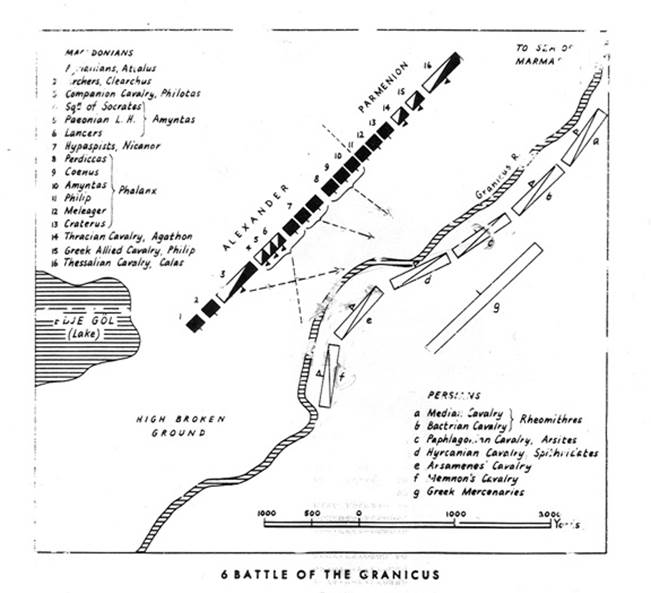

Macedonian

forces: 32000 infantry, 5100 cavalry, plus navy and allied forces = 90000

total. Persian forces 20000 cavalry and approximately the same number of

infantry. His siege train also included haulers, engineers, surveyors, camp

planners, a secretariat, court officials, medical staff, grooms for the cavalry

and muleteers for the baggage. Some 182 war ships and supply vessels supported

his force, 160 allied warships. Alexander arrived in Bithynia with 70 talents

in bullion and sufficient supplies for 30 days’ campaign. Memnon, a Greek

mercenary commander serving with the Persians, recommended a strategy of

calculated retreat with scorched earth, but Persian commanders, many closely

related to King Darius III, insisted on a confrontation and chose the Granicus

River. Alexander left 12000 infantry, 1500 horse with Antipater in Macedonia.

Recorded

force components: 12000 Macedonian Pezhetairoi; 7000 allied infantry; 5000

mercenary infantry all under Parmenio; Odrysians Triballians, Illyrians = 7000;

archers and Agrianians 1000 = 3200; cavalry 1800 hetairoi under Philotas; 1800

Thessalians, under Callas son of Harpalus; 600 Greek cavalry under Erigyius;

900 Thracians and Paeaonian scouts under Cassander, equaling a sum total of

5100 cavalry. Parmenio recommended a delayed night crossing down river, but

Alexander overruled him. He ordered a direct assault on the Persian formation

arranged on the opposite bank of the river.

Plut:

Alexander immediately plunged down the bank and into the water with 13

squadrons into swiftly flowing water that surged about them and swept men off

their feet. Despite this he pressed forward and with a tremendous effort

attained the opposite bank which was a wet treacherous slope covered with mud.

There he was immediately forced to engage the enemy in a confused hand to hand

struggle, before the troops who were crossing behind him could be organized

into any formation. The moment his men set foot on land the enemy attacked them

with loud shouts matching horse against horse, thrusting with their lances and

fighting with the sword when their lances broke. Many of them charged against

Alexander himself, for he was easily recognizable by his shield and by the tall

white plume which was fixed on either side of his helmet. His breast plate was

pierced by a javelin. Spithradates (a Persian noble) rode at him, and hit him

on head with a battle axe, splitting the crest of his helmet. Cleitus the

Black, the brother of Alexander’s wet nurse, ran him through and saved

Alexander’s life. While Alexander’s cavalry was engaged in this furious and

dangerous action, the Macedonian phalanx crossed the river and the infantry of

both sides joined the battle. The Persians offered little resistance but

quickly broke and fled, and it was only the Greek mercenaries who held their

ground. The latter fought to the death.

The Persians lost 20000 infantry and 2500 horse; Alexander lost 34

cavalry, 9 in the infantry. Captured

shields were sent to

Arrian

1.13-15: the cavalry charged in a wedged formation. [The Persian cavalry was

arranged in a line 16 deep; the Macedonian phalanx was arranged 8 deep;

Alexander’s cavalry unit was arranged 10 deep.] Alexander led the cavalry in an

oblique attack across the water so that the army would not get flanked: oblique

to the current. This enabled him to prevent a flank attack as he emerged from

the water and to engage the enemy with a front as solid as he could make it.

The Persians were arranged with mounted troops in front and infantry to the

rear…it was a cavalry battle with, as it were, infantry tactics: horse against

horse, man against man, locked together. The Macedonians did their utmost to

thrust the enemy once and for all back from the river bank and to force him

into open ground; whereas, the Persians fought to prevent the landings or to

hurl their opponents back into the water.

The

Greek mercenaries fight to the death because of Philip II’s warning that all

Greeks who supported the Persians would be executed. Some 2000 were enslaved

and sent to Macedonia.

Alexander in

Greek

cities paid taxes to him as their “liberator”; non Greek peoples paid tribute.

He freed

He

suppressed internal conflicts in cities and won the respect of native peoples.

He was adopted by

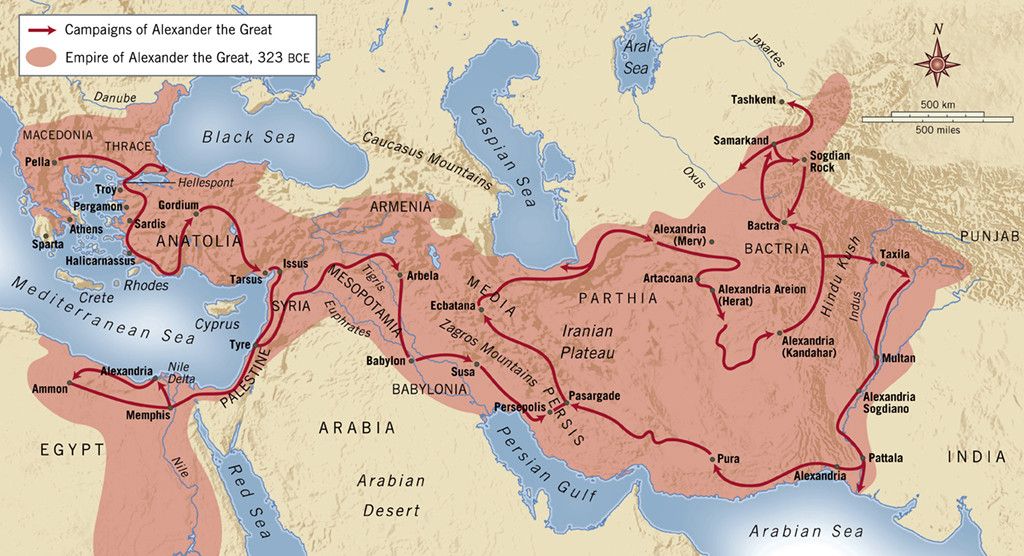

The Strategic Threat: Persian army could invade

from the Anatolian Plateau; the Persian Navy from along the coast. Alexander’s

solution, to seize the “rail heads” of the interior (Dascylium, Sardis) and to

deny the Persian fleet any coastal safe harbors.

Siege

of Miletus, he brought his fleet of 160 warships to Lade, 3 days later a

Persian fleet of 400 arrived. Alexander avoided a sea battle and concentrated

on a siege of the city with his fleet blocking the harbor. The Persian garrison

surrendered. Alexander now had Persian granaries to feed his army, so he

dismissed his fleet (he could not afford to keep it in any event; though he

kept 20 Athenian triremes for good behavior). Tribute and contributions now

arrived from various parties. The Persian fleet were left with no port

facilities in the Aegean.

Situated on a peninsula south

of Miletus, Halicarnassus was a crucial port to take, controlling passage to

much of the rest of Persia. The city was

also the best defended, boasting a naturally strong position, along the edge of

rolling hills on all sides, and three inner fortresses, rather than a single

acropolis. Bringing siege engines close

to the walls would be difficult, and invite a barrage of missile fire with each

assault. In addition to the city’s

natural defenses, preparation for Alexander’s attack had contributed to make

the port near impenetrable. The walls

were surrounded by a moat, 13m deep, which would prevent siege engines from

reaching the walls, and further serve to delay and deter attackers. In addition, the full Persian fleet waited in

and around the harbor, some 400 warships keeping hold of the city’s connections

over sea. While this placement was

largely unnecessary, due to the Macedonian fleet’s dismissal, the warships

maintained the largest advantage for Halicarnassus: a supply route that Alexander could not hope

to halt. Any assault on Halicarnassus

without a navy would have to be made against a fully stocked and prepared

defense. Perhaps the greatest threat at

the Halicarnassians’ disposal was their leader:

the Greek mercenary general Memnon.

One of the most experienced mercenaries in service to Persia, Memnon had

served Artabazus in 353, in a rebellion against Artaxerxes III, king of

Persia. After this failed, Memnon, and

his brother Mentor, were exiled from Persia, and the two found their way to the

young King Philip’s court in Macedonia, where they learned of Philip’s arching

plan to take Greece, and move into Persia.

Armed with this information, the two were soon pardoned by Artaxerxes,

and welcomed back. Memnon’s advice was ignored by the Persian hierarchy at the

Battle of the Granicus R.

Though the Persian navy, sent

by Darius, had arrived too late to save the town of Miletus, which fell to

Alexander’s onslaught with ease, the fleet regrouped with Memnon, who had made

a point of gathering mercenaries from Alexander’s fallen cities, at

Halicarnassus. Memnon, around this time,

sent his family to live with Darius, to earn the King’s trust. With hostages, of sorts, held over the

mercenary, Darius felt safe in naming Memnon supreme commander of the west,

though perhaps at too late a time.

Memnon took over operations at Halicarnassus, and quickly set to work

reinforcing walls, fixing any point at which he found weakness. The Macedonians, meanwhile, had arrived on

the outskirts of the city, setting up camp around a kilometer away from the

eastern gate, facing Mylasa. This gate

would prove to bear the brunt of the attack.

With his siege engines still in Miletus, Alexander decided to send them

by sea to Halicarnassus. Given the

presence of Persian warships, this move was a risk, but, for Alexander to be

victorious, the city would have to fall quickly.

Speed was key to Alexander’s

assault, as any time granted could allow the Persians to regroup and set up a

plan to stop the Macedonian rush along the coast. Memnon, conversely, knew that, while he could

not hold the city against Alexander’s superior forces, he could delay, forcing

a long siege and taxing the Macedonian supplies. This would both give an opportunity for the

defenders to escape and grant the Persians a much-needed break in the

Macedonian onslaught. Memnon’s plan to

force a lengthy battle was begun shortly after the Macedonians had set up

camp. A group of missile troops issued

out of the Mylasa gate, struck from the hills down to Alexander’s camp, and

quickly retreated within the walls.

While this early encounter led to little in the way of casualties, it

was very representative of what Memnon’s tactics would be: quick, missile-heavy skirmishes, to harass

the besiegers, and retreat before a full-scale fight began, in which the heavy

infantry of Alexander would have a clear upper hand. After dealing with the skirmish, Alexander

began to set his own plans for the siege in motion. He lost precious time attacking nearby

Myndos, and then attempted an assault on the Halicarnassus defenses without the

benefit of siege weaponry. Eventually, his siege weaponry arrived from Miletus and the siege

began in earnest.

Halicarnassos, walls reportedly 150 ft

high, Alexander assaulted the defenses with siege weaponry and 20 Athenian

triremes. He was able to take the lower city but not the acropolis which

guarded the harbor (Memnon was commanding the resistance; he was now in command

of the Persian fleet and lower

Parmenio

was dispatched into the plateau from

During

the winter 334/3 BC, a Persian agent named Sisenes was arrested by Parmenio

with a plan to kill Alexander. Allegedly he was caught while communicating with

Alexander the Lyncestrian and Amyntas. Amyntas was the former friend of Amyntas

the prince (nephew to Philip II) who fled to the Persian side at the time of

the assassination. He was captured while

infiltrating the camp, allegedly communicating with Alexander the Lyncestrian. Alexander had Parmenio arrest

the Lyncestrian (who was then commanding the Thessalian cavalry); Amyntas was

executed. Olympias had written Alexander warning of this plot. Parmenio was in

Winter

334/3 Memnon sailed with 700 warships from