CLASSICAL CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

The Great Wall of China at the Nank'ou Pass, Chih-li; 228 BC. The wall is 1,400 miles long, with square watch-towers at intervals. (From Chinese Art: London, 1932, Plate I)

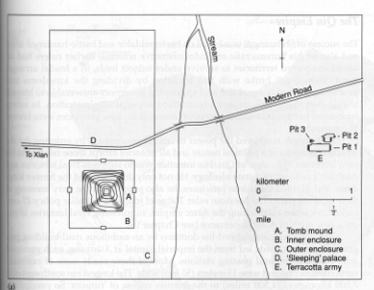

LEFT: View of plan of the tomb of Emperor Qin Shihuangdi , first emperor of China (221-210 BC). His burial mound 40 km. outside Xian was 50 m. tall. Around its base stood two huge rectangular enclosures one inside another, 2 km square. Between the outer and inner walls stood a "sleeping palace" occupied by guards, attendants, and concubines who tended the grave of the dead ruler. 700,000 convicts were allegedly conscripted to complete the burial complex. Greatest tomb ever built in China; never fully excavated. RIGHT: View of similar mound and processional way of tomb of Koa-tsung (d. 683 AD) and Wu Tse-t'ien (d. 705), Ch'ien-hsien, Shensi. (From M. Sullivan, The Arts of China, 3rd Ed., Berkeley, 1984, fig. 145).

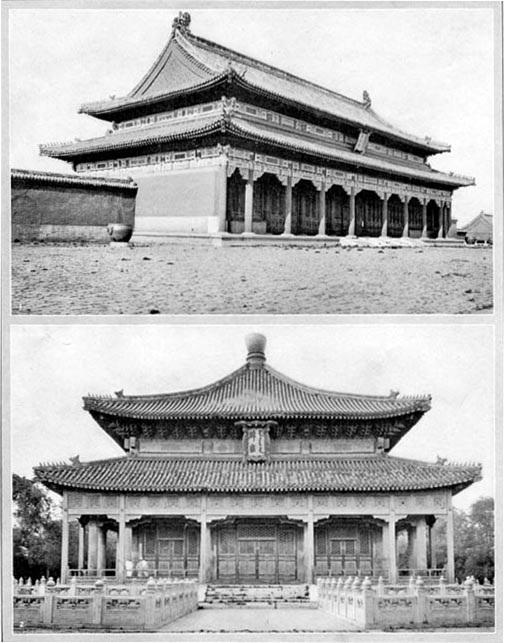

Two Great halls or tien in Peking: Pao Ho Tien, one of the Three Great Halls in the Forbidden City (1627 AD), and the Hall of Classics, at the Confucius Temple (Chinese Art, Plate VIII). An oblong rectangular room divided by rows of round pillars or columns into three or more naves of which the foremost was usually arranged as an open portico. The interior is, as a rule, lighted by small, low windows. Very important for the decorative effect of the building is the broad substructure, the terrace, and the far projecting roof. When the substructure is made higher, a so-called t'ai is created, that is, a shorter hall or a centralized building in two stories on a high terrace with battered walls. The upturned lines of roof corners suggest aspiration. The tent form is sometimes regarded as the possible origin of the characteristic shape of Chinese roofs.

Plan of the Lin-te-tien of the Ta-ming Kung, Ch'ang-an, T'ang Dynasty (8th century AD). Characteristic of all extensive Chinese compounds is the clear development of a main central axis running north/south. The principal buildings, their courts and gateways are all placed in a row, one behind the other, while the secondary buildings are arranged at the sides of the courtyards. The facades, the doors and the gates of the principal buildings all face south, an orientation which was evidently based on religious traditions. The architectural compositions were enlarged by joining more courts. Interlocking of masses on ascending levels buttressed at the sides by wings and towers lends strength to the complex. (Sullivan, Arts of China, fig. 149)