Course Materials

List of Good, Interesting, and Relevant to the Course Art

Announcements and Other Stuff

• Recent stuff on the workism and authenticity angles:

• The dark shadow in the injunction to 'do what you love’

• A very good episode of Ezra Klein's podcast on Work as identity, burnout as lifestyle

• For Simone de Beauvoir, authentic love is an ethical undertaking: it can be spoilt by devotion as much as by selfishness

• A final few things that came up in our last session with Professor Ware:

• Professor Ware recommended a favorite book of his called The Rhetoric of Motives by Kenneth Burke, specifically a short chapter about identification. It's here.

• The Ted Talk that Eva mentioned, about Lollipop Moments given by Drew Dudley.

• A

story about one of my own lollipop moments seems appropriate to share

here. It is a favorite story/piece of advice from one of my philosophy

professors right before I was graduating from college. It stuck with me

(obviously), but when I saw him years later, he didn't even remember

telling it to me:

• The New Yorker put together a pretty good video

that goes through some of the main themes of Storr's book on

narcissism, individualism, and selfies. In his interview, with

Illing at vox, Storr makes a claim that is interesting, even if I'm

inclined to think it's overly simplified and misleading, namely that

the selfie camera didn't "create this narcissism; it simply gave us a

new device to amplify it. … I think technology just shows us who we

are; it doesn't change who we are."

• For a while now I've found myself wondering if meritocracy was a reasonable and laudable ideal, and the problem was that our society was failing in all kinds of ways to live up to it, or rather if, for some reason, meritocracy was an inherently corrupt ideal to begin with. In an overview of his book The Meritocracy Trap Daniel Markovits argues for the latter of those two. In doing so, he provides a set of arguments that seem to intersect in interesting ways with a lot of the points that Thompson makes in his essay on "workism", not to mention Tolentino's idea that we have created "a world in which selfhood has become capitalism's last natural resource", and William Deresiewicz's idea that our educational institutions are currently set up to shape students not into independent and critical thinkers but rather into Excellent Sheep:

"A person whose wealth and status depend on her human capital simply cannot afford to consult her own interests or passions in choosing her job. Instead, she must approach work as an opportunity to extract value from her human capital, especially if she wants an income sufficient to buy her children the type of schooling that secured her own eliteness. She must devote herself to a narrowly restricted class of high-paying jobs, concentrated in finance, management, law, and medicine. Whereas aristocrats once considered themselves a leisure class, meritocrats work with unprecedented intensity."

"A

person who extracts income and status from his own human capital places

himself, quite literally, at the disposal of others—he uses himself up.

Elite students desperately fear failure and crave the conventional

markers of success, even as they see through and publicly deride mere

"gold star" and "shiny things." Elite workers, for their part, find it

harder and harder to pursue genuine passions or gain meaning through

their work. Meritocracy traps entire generations inside demeaning fears

and inauthentic ambitions: always hungry but never finding, or even

knowing, the right food."

• Like I mentioned in lecture, I worry that it can start to feel like this but appreciating individualism and how deeply it structures our lives and selves and institutions can make you start seeing its manifestations everywhere. Here is another place: housing. This article doesn't explicitly name individualism as a culprit, but it suggests that even something as structural as our collectively shared preferences for where and in what kind of buliding to live -- the "American Dream" of owning your own home -- seems to be a reflection of individualism and self-reliance. And it also seems like it generates a lot of the same downsides and costs of individualism in other areas: atomization, isolation, lose of community, and all the unpleasant effects that comes with those types of social deprivations.

• Speaking of workism and code-switching and psychological compartmentalization and the dissociative effectives of masks, here are a couple of write ups that look an unsettling relationship between people and a particaulr kind of job, namely: Investment Bankers Severely Dissociate Their Sense of Self from Their Work.

• The

piece we read by Jennifer Morton on code-switching is part of a larger

argument about higher eduction and social mobility, which she lays out

in her book Moving Up without Losing Your Way: The Ethical Costs of Upward Mobility. That book has been getting some love and making some waves in the larger, non-academic press too. In this interview with The Atlantic, she talks about growing up in Lima, Peru, and about The Price of Ascending America's Class Ladder.

• Here is an interesting opinion piece arguing that framing the problems surrounding social media use and abuse in terms of *addiction* might be misleading. Rather, it argues that it's not addiction or social media itself that lies at the root of the problem, but unhealth social norms about how to interact with social media, and how the pressure to comply with those norms taxes our social emotions. The book I mentioned in the context of our conversation about this - the one about people who get so immersed in electronic gambling machines that it is not uncommon for them to wet themselves and keep playing - is Addiction by Design by Natasha Dow Shüll. She is an NYU sociologist whose next book project is on the technological aspects of self-care, self-improvement, and what's become known as the quantified self movement. She has a nice lecture here on Lifestyle Algorithms: Wearable Technology and Self-Regulation.

•

Remember that on Tuesday November 19th we will meet in Stewart G52.

Linda Woodhead will be teleconferencing in from the Lancaster

University in the UK, todiscuss her project on GenZ. In

preparation, of course do the two readings but also please reflect on

the majesty of this meme:

• An interesting idea from the Renner reading on what social media does to identity focused on a key shift to adolescence:

"Everyone

... benefits from experimentation in adolescence. During that time, we

exist in what the psychoanalyst Erik Erikson called a psychosocial

“moratorium”—a stage in which we hover “between the morality learned by

the child and the ethics to be developed by the adult.” The moratorium

is a period of trial and error that society allows adolescents, who are

permitted to take risks without fear of consequence, in hopes that

doing so will clarify a “core self—a personal sense of what gives life

meaning.” The Internet interrupts the privacy of this era; it tends to

scale up mistakes to monumental proportions, and to put them on our

permanent records."

The

focus on the issue of privacy reminded me of an article about the

importance of secrets to psychological development from a couple of

years ago. To the extent that

parents don't let their kids keep secrets, they are stunting their

grown and the emergece of their private, inner lives - and thus their

autonomy and independence of mind: or so argues Tiffany Jenkins in her

essay My secret life.

• New work on cultural evolution and WEIRD psychology making it to the mainstream news on NPR: Western Individualism May Have Roots In The Medieval Church's Obsession With Incest. It also got a nice write up by Michelle Gelfand, who does interdisciplinary work on social norms: Explaining the puzzle of human diversity: Centuries of Church exposure promote more individualistic and less conforming psychology. The paper itself, and a link to its enormous body of data, is here: The Church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation.

• The HBO documentary is

riveting: The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley. The whole (ongoing) saga is so engrossing that there is

also a bestselling book Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup,

which is already being turned into a movie

starring Jennifer Lawrence.

• Two threads from Callcut's discussion of Gauguin, mid-life crises, moral luck, and the toxic side of authenticity:

Callcut links to a recent philosophical analysis of jerks by Eric Schwitzgebel. It came out around the same time that Aaron James, another professional philosopher, published a book on Assholes. In terms of approach, aims, and subject matter, these are in the same neighborhood as Harry Frankfurt's classic On Bullshit and Nick Riggle's article and book on Awesomness and Suckitude. They are doing serious analysis of the concepts and vernacular terms we use to think about social values and assess each other as persons. These analyses typically go on to reflect on what the ascendancy of those values tell us about the state of our culture and our selves. FWIW, since people have been making careful distinctions between jerks, assholes, bullshitters, and people who suck, I've wondered what it is that's distinctive of douch bags. As far as I know, no one has yet tackled this important question.

Callcut also discusses philosopher Kate Manne's concept of 'himpathy'. Manne has deservedly risen to superstar public intellectual status on the wave of the attention lavished on her book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny

• For a

very of the moment example with to meditate on Trilling's the claim

that the idea of villains and villainy initially emerged from a concern

with dissembling and insincerity, you could do much worse than the

story of Theranos and Elizabeth Holmes. The HBO documentary is

riveting: The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley. The whole (ongoing) saga is so engrossing that there is

also a bestselling book Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup,

which is already being turned into a movie

starring Jennifer Lawrence.

• A personality isn't quite the same thing as a self or an identity in the sense that we've been discussing, but it's not entirely clear what the connection is, either.

Here is a write up of the longest running personality study ever, which tracked the personality traits (self-confidence, perseverance, stability of moods, conscientiousness, originality, and desire to learn) of a cohort of participants from the time they were 14 until they were 77. The lack of any correlation between individuals' traits at those two time slices inspired the sensationalistic headline "You're a completely different person at 14 and 77"

Here's an interesting podcast that starts with the Harry Potter "sorting hat"and asks why we're so fascinated with personality testing even though a lot of the more pop versions - including the famous Myers-Briggs one, which is probably more self-help than science - lack any kind of psychometric validity. They're ubiquitous in office management, to the extent that the NYTimes just ran a piece calling personality tests "the astrology of the office".

On the more empirically and statistically rigorous side, while the personality categorization based on the Big Five OCEAN traits

seems legit, personality science remains somewhat vexed. A recently

published and fascinating new paper argues that even OCEAN personality

structure might be

parochial to WEIRD cultures, more a function of variable external

factors like niche diversity and social complexity than anything internal to individuals, or the expressions

of timeless, innate, and universal features of human psychology.

• The more triumphal verisons of the story of the rise of modern individualism in the West typically portray it as a story of liberation. Opportunities for personal freedom and liberty increase as previously stable forms of social organization break down, and individuals are released from the shackles of conformity, hierarchy, rigid traditions and stifling social roles. This is a tradeoff, of course, and places new demands on those individuals. One of what I've been calling the imperatives of individualism is that you get to choose more, but that has a flip side as well - individuals also have to choose! choose! choose! This can start to feel like a new and different kind of coercion. It can be anxiety producing and exhausting. Theorists of different sorts have tried to take the measure of this new package of challenges. Psychologist Barry Schwartz (no relation to Alexandra) studies it under the heading the paradox of choice, and as Eva pointed out, has a very good TED talk about it. The philosophers Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Kelly (no relation to me) examine some of the philosophical and literary history behind it under the heading of the burden of choice.

• A couple of interesting recent companion pieces to our discussions (of narrative selves, of attention, of the role of social media in shaping both):

A fantastic one called Disarming the Weapons of Mass Distraction that focuses on what social media is doing to our attention (and thus ourselves?) "Attention is the real currency of the future. ... Attention is a complex interaction between memory and perception, in which we continually select what to notice, thus finding the material which correlates in some way with past experience. In this way, patterns develop in the mind. We are always making meaning from the overwhelming raw data. ... Another point is less often emphasized. Ignoring something requires a form of attention. It costs us attention to ignore something. Many of us live and work in environments that require us to ignore a huge amount of information—that flashing advert, a bouncing icon or pop-up." I really like the idea of reestablishing an attentional commons, taking back the right to not be addressed.

Philosopher

Carolyn Dicey Jennings as been asking the question "what is the self if

not that which pays attention?", and framing her answer as a riff on an

old familar theme: "I attend, therefore I am"

Another on A revolution in our sense of self that looks like it would be interesting to think about in conjuction with the idea from Jaynes and cultural and literary scholars about the 'creation' of interior subjectivity, and tha might be trouble for the very idea of a Deep or True Inner Self - "In a radical reassessment of how the mind works, a leading behavioural scientist argues the idea of a deep inner life is an illusion. This is cause for celebration, he says, not despair."

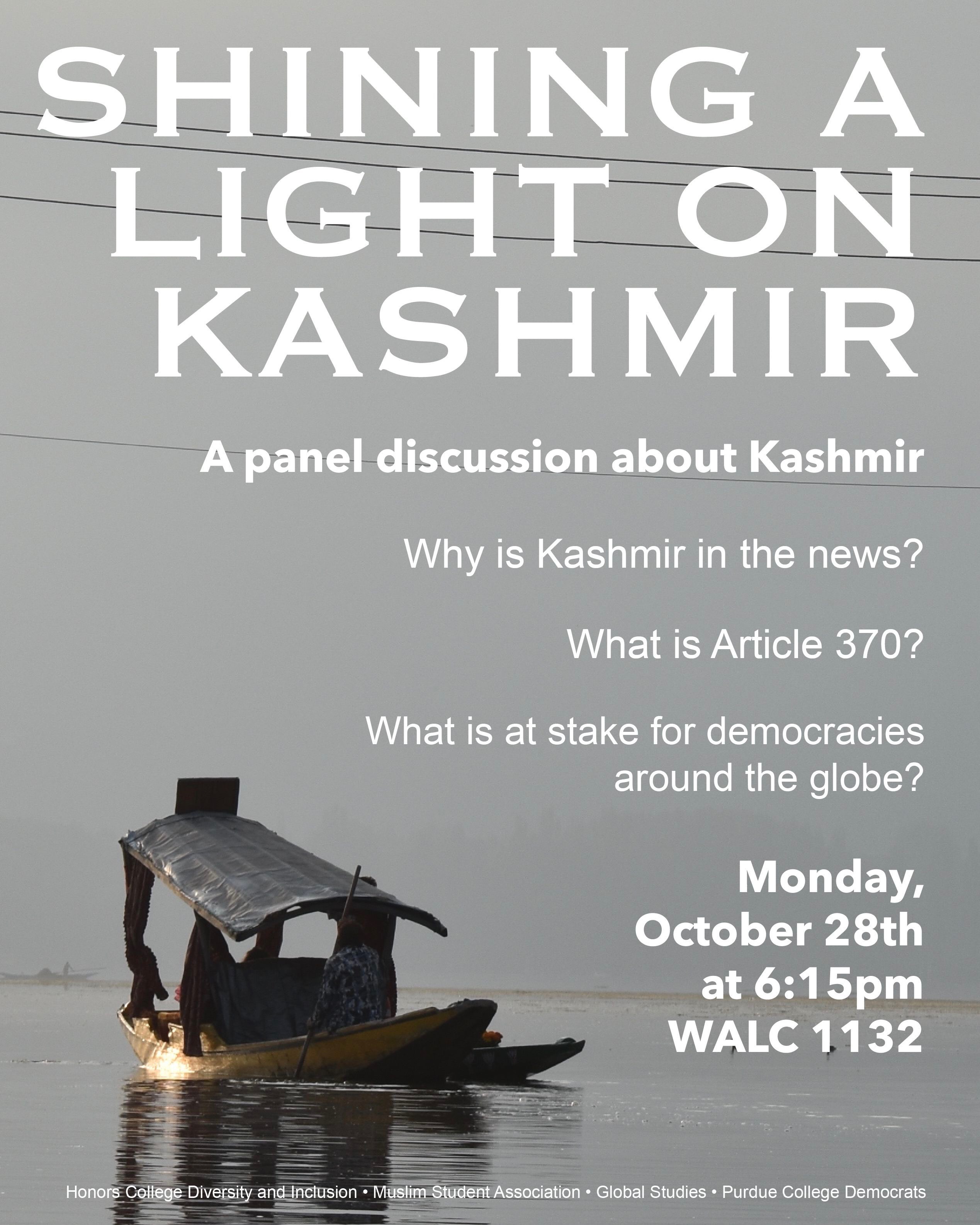

• Come out for this event next week! Think about it in the context of justice and human rights and the kind of individualism so central to Western political systems! Attendance will count as one (1) outline!

• A

great question from last week was whether or not the kind of WEIRD,

hyperindividualistic culture we currently inhabit is likely to have a

higher prevalence of mental illness than less WEIRD, more collectivist

cultures. There is a nice discussion of a fascinating book, Crazy Like Us: The

Globalization of the American Psyche, that

addresses this cluster of issues here.

This and other research suggests that even the forms

that mental illnesses takes can vary from culture to culture, resulting

in what are called "culture-bound syndromes". For example, consider running amok

or The Truman Show Delusion.

• Term Papers and Prospectus

• Final papers will be due on Monday December 9th

You can email them to me

They should be 8-10 pages long

Topics are open ended, of your own choosing

The paper and thesis should be connected to the themes of the course and draw on some of the readings, though not restricted to them - you are encouraged to bring in further resources as well

You can build on and/or expand a position paper if you are

still interested in the debate you addressed in one of those

• Prospectus are due in class on Tuesday November 12th

If you have never written a prospectus before, I've gathered together some guidelines here

Please feel free to talk to or email me if you'd like to

discuss potential paper topics, structure

• Julian

Jaynes thought humans weren't conscious until about 3000 years ago, and

until then they were just very sophisticated automata, lacking

interiority, inner self-awareness, and individual initiative and

autonomy -- sort of sleepwalking through life. Thomas Metzinger

thinks that actually most of us are still sort of sleepingwalking

through life, or at least are sort of sleepwalking through life way

more than we realizee: Are you sleepwalking now? Given how little control we have

of our wandering minds, how can we cultivate real mental autonomy?

• For

those of you interested in hallucinations, psychedelics, and what they

tell us about the nature of the self (with a touch of predictive

processing theory in there as well), this article

on self models and ego dissolution is pretty great, and weaves together

a lot of promising, and to us familiar, ideas together very well.

Michael Pollan's recent book on

the history of psychedelic research, trascendent experience, and the

new research on its shockingly effective use in therapy to treat

conditions like PTSD, depression, and anxiety is also a fascinating and

good read.

•Aeon Magazine just published an article that connects up to our set of themes, how selves are collaborative constructions built socially with others, and how stories are crucial to their nature: My friend, my self: Female friendship is central to much recent fiction and film. What can it say about the role of relationships in identity? I am happy to confirm that her two main examples--Ferrante's Neapolitan novels and Waller-Bridge's Fleabag--are indeed both fantastic.

• This

recent essay, Fascinated to Presume: In Defense of Fiction by

novelist Zadie Smith, is breathtakingly good. It discusses how novels

interact with selves, how many people are plural and have a number of

different voices in their heads, and how it all interacts with the

current climate in which much of what novelists do might seem to run

afoul of emerging norms that monitor cultural appropriation.

• An interesting essay published over the break: How science has shifted our sense of identity: Biological advances have repeatedly changed who we think we are.

• Lab rats play hide and seek for the fun of it! As the article notes, this suggests that even rats have some rudimentary versions of the psychological capacities that underlie identity and sociality, especially the ability to understand the rules of the game (a kind of social norm, which loom large in both Witt and Ross's theories) and the ability to understand the difference between the hider and the seeker (a kind of social role, which loom large in Witt's theory).

• The podcast Radiolab has a great episode on Placebo Effects and other self fulfilling prophecies. Radiolab's very first episode was on the self, and called "Who am I?"

• A

super interesting and timely article on the phenomenon researchers have

dubbed identity fusion

which they describe as the 'most dangerous way to lose yourself'. The

researchers look at cases where "out of a basic need for consistency,

we might take on other identities as our own." The article claims this

happens due to "a fundamental “desire to be known and understood by

others." Self-views enable us to make predictions about our world and

guide our behavior. They maintain a sense of continuity and order.

Stable self-views also, ideally, help facilitate relationships and

group dynamics. When people know their role in any particular dynamic,

they predictably play the part, even when doing so is self-destructive.

Self-views seem to have their basis in how others treat us, and they

solidify as we accept our position and behave to further warrant

similar treatment. An overall sense of identity comes together like a

patchwork quilt of group and self, defined by where we fit into the

world. Each of us is someone's child, someone's neighbor; a member of

some community or religious sect; we are the work we do, the dogs we

have, the places we've lived, the bands we listen to and teams we cheer

for and authors we keep on our shelves."

• The

article I mentioned in class on Tuesday, in the context of talking

about why philosophers and psychologists get so interested in odd

examples and cases (Hannah Up, Susie McKinnon, dissociative disorders)

and hypothetical, fictional, and even science-fiction-y cases

(malfunctioning teletransporters, uploading your mind onto a computer,

etc.). What's fictional and hypothetical today might not be either in

the not so distant future: Brain-reading tech is coming. The law is

not ready to protect us. In the era of neurocapitalism, your brain

needs new rights

• A

useful distinction we saw in discussing the Lockean questions about

personal identity and continuity was between qualitative

identity - which holds between two things just in case they share ALL

of their qualities, are completely similar in every respect - and numerical

identity - which holds between two things just in case they count as

... the same thing. But obviously what kind of 'thing' we are talking

about, what concept we

are using, matters. In response to Locke's question, we looked at

theories about when two persons (or person stages) count as the same person; not the same body, not the same collection of molecules, not the

same human being - the same person. You can do it with other

concepts, too: is Istabul the same city

as Constantinople? Another famous philsophical puzzle that raises

questions about numerical identity is The Ship of Theseus

- how much about a ship can

you change, and what parts, such that it still be the same ship? A longer discussion of

this puzzle is here.

•

Lindemann's theory is deeply socially, and fundamentally committed to

the idea the personhood and identity of any particular individual is

secured by their relationships to other people. In the final couple of

pages, she recognizes that the theory is incomplete, part of a much

larger tapestry of relations. In one interesting passage: "I've said

too little about the things aside from people that hold us in our

identities. A piece of land, a house, a neighborhood, an office—these

can all proclaim or remind us of who we are, so that if they are

invaded or taken from us, we feel personally violated. The material

objects that furnish these places can also play a role in maintaining

our identities. Familiar routines are important as well, as are hobbies

and (for some of us) scholarly interests. So are impersonal

institutions such as banking and the stock market." (204). The part

about material objects especially reminded me of the Extended Mind

thesis, and of this recent Aeon Magazine article

whose tagline is "I am my things and my things are me. I don't want to

give them up: they are narrative prompts for the story of my life."

• Lindemann's account of personhood and identity draws

on lots of theatrical imagery and language: "Personhood,

on my Wittgensteinian account, is a matter of expression and

recognition, of playing roles in a kind of human drama." (16). She

explicitly builds on the enormously influential philosopher Ludwig

Wittgenstein, but another important theorist in this tradition of

thinking about the nature of persons, selves, and identities is the

psychologist Erving Goffman.

Goffman's 'dramaturgical' model of social interactions is spelled out

in his book The Presentation of the

Self in Everyday Life. The video in that link points out (as

have numerous scholars),

this mode of thought can be traced back centuries, and is

nicely encapsulated by Shakespeare's aphorism "All the world's a

stage". Also, Elvis.

• Memory

is so hot right now! As a topic of research, anyway. As I mentioned in

repsonse to many of your outlines, and the puzzling case of Susie

McKinnon, there are currently debates about what this recent book review

describes as "an intriguing phenomenon: the fact that we often remember

autobiographical episodic memories, both voluntarily and involuntarily,

from a point of view other than the one from which we experienced the

original event. Known in the psychological literature as the

field/observer distinction, memory's capacity to shift perspectives has

intrigued researchers".

• Here

is a nice Aeon Magazine interview with philosopher Andy Clark

discussing uploading your mind to a computer, malfunctioning

teletransporters, and other

puzzles associated with memory-based theories of Lockean personal

identity through

time. Clark is most famous for his defense and exploration of The

Extended Mind hypothesis that seem implies that strictly speaking your smartphone might really be part of you

and your mind, despite being external

to your skin and skull.

• Speaking of expanding the moral circle and including more entities in the category of persons, in New Zealand a river was recently granted the status of personhood: "The legislation, which has yet to be codified into domestic law, refers to the river as an “indivisible, living whole," conferring it "all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities" of an individual."

• Humans, of course, are paradigmatic instances of persons, from a moral and common sense point of view. But from a legal point of view, corporation and companies are persons as well, at least in the United States. It's a key element in the debates that swirl around the Supreme Court decision on Citizens United, political contributions, dark money, etc. Roughly, from a legal point of view, corporations are persons, and so corporate financial contributions to political causes are in some cases deemed legal because they are classified as a form of speech and political expression - and so protected under the laws that protect the right to free speech and free expression that all persons have. Another philosophically interesting appearance of applications of the concept of personhood in the legal domain comes from Canada, where the fight to get chimpanzees all the legal rights and recognitions of personhood continues.

• Here

is the near finalized schedule for Flash Presentations,

which includes not just week but day of the week (Tues or Thurs).

Remember to schedule an appointment to do a test run of your

presentation with the the Purdue Presentation Center

beforehand, and bring to class whatever documentation they provide.

• Don Ross thinks elephants have the cognitive capabilities required to count as persons, and that one of those capabilities is sophisticated language. Of course he doesn't think they communicate to each other verbally the same way we do, but with some complicated cross-modal language that he wants to decode, so he can help them into even higher reaches of personhood. But his case that they have linguistic abilities that can sustain displaced reference (talking about things that are not immediately present to them) and syntax structured semantics (putting together words and symbols to express complex thoughts) turns heavily on how they use vibrations to transmit information to each other, as discussed in this cool video How Elephants Listen ... with Their Feet.

• Here's

a short youtube video I showed in class on Thursday that also gives an

overview of The

Secret to Our Sucess: How Culture is Driving Human Evolution,

Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. It describes some

key ideas of the currently most promising theory about how human minds

evolved and what's

so special about them (there's a discussion on the evolution website This View of Life,

too).

• It

came up in class on Thursday, so here's good

piece on the creepy phenomenon of phantom

limbs and phantom pain. It also has a

discussion some pretty cool lo-fi mirror involving ways of getting rid

of them. A related, creepy, but less tragic phenomenon is the rubber hand illusion.

• The Descartes edition of Three Minute Philosophy - funny, and gets a surprisingly large amount basically right. (Warning: contains some strong language and mild funny-making.) Here's another video about Descartes and the cogito.

• Neal

(or Neal's Ghost, whoever the initial narrator of Good Old Neon is)

describes what he calls the 'fraudulence paradox'. It isn't quite the

same thing

as what's called the imposter syndrome, but they're in the same

neighborhood. Both have to do with a disconnect between how

someone feels on the inside and how they present themselves to the

outer world, how they see themselves versus the impression that create

in others, or fear they're presenting in other people. I've

posted a nice paper on imposter syndrome in the online readings by

Sarah Paul. Aeon Magazine

published an article last year by philosopher Amy Olberding that deals

with it from a pretty interesting angle, too. There's also this Clance Impostor Phenomenon Test you can take in a

couple of minutes if you're keen.

• Here's

a pretty good short video that

talks about selves and fills in some background about Socrates and the

Oracle at Delphi, associated with gnomic aphorisms like "the unexamined

life is not worth living" and "know thyself", respectively. It also has

a nice discussion of the kind of view that Ismael calls "nolipsism" in

the selection of hers we read, e.g. the view that modern science is

revealing that there's no such thing as a self, that it's all just an

illusion. She rejects that view, of course!

• That

picture on my homepage was taken the aptly named Blue Pool at Tamolitch Falls in

Oregon.

• Our

first class will be

Tuesday 8/20 at 10:30pm in HCRN 1143, in the Honors College and

Residences North Building.

Course Description

What

makes you distinctively and uniquely you? How can you be a part of the

same person as the 7-year-old version of yourself, given how much

you’ve changed physically and mentally? How are the inner, subjective

parts of yourself related to the many different faces you present to

the outer world and the various social groups you move through? What

are the special features of human minds that enable us to maintain such

multifaceted identities and to juggle these different aspects of

ourselves? What is it about the structure of our social lives that

requires us to do the juggling? Has it always been like this? Given

that we can do it, and these days we pretty much have to do it, what’s

the best way to do it? How should our inner and outer aspects be

related and juggled? How might ideals like authenticity and sincerity

help us to better guide the coordination of the private and public

sides of ourselves? What was Emerson suggesting when he famously

claimed that a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds?

‘Consistency’ is obviously an important virtue, but the ‘foolish’ part

seems key, too.

What

is a self, and where does it come from? How much of your identity is

given, and how much is chosen, constructed, and achieved? What form

does the given part take? How much of the construction part is done in

collaboration with friends, family, and other people? What are the

construction materials? Where do they come from, and what exactly do

you use them to do? How does our contemporary culture contribute to the

pool of materials and shape the space of options you have to choose

from? How did we get to our current moment in history, with its

individualistic selves and buffet of identities? How did the modern

ideals of liberty, unfettered choice, personal freedom, and individual

responsibility coalesce into their current form and ascend to their

place of cultural prominence? What are today’s most striking

manifestations of the deep-seated and distinctively American values of

rugged individualism and self-reliance? How have technological advances

like social media transformed the challenges that stand in the way of

being genuine, and of fully and successfully following Nietzsche’s

famous exhortation to Become Who You Are?

This

course will develop some conceptual resources for addressing with these

questions. We won’t be bothered by disciplinary boundaries, but will

instead help ourselves to whatever ideas are most useful and best

suited to our concerns. We’ll draw on work by philosophers, cognitive

scientists, anthropologists, social and literary historians, cultural

evolutionists, and contemporary essayists to help us grapple with these

issues. They will all be necessary because questions don’t get much

bigger than these. They are enormously challenging, intellectually

puzzling, and deeply personal all at once.

Thinking about picking up a major or minor in Philosophy? Good Idea!

• Editorial Note:

I recall well that even if you are attracted to philosophy for the

sorts of timeless intellectual reasons that Bertrand

Russell

pointed to a century ago, it is not always obvious

what you can do with a degree in philosophy after you graduate. This is

worth thinking about! And so here is a thought: what philosophy has going for it, and

perhaps going for it more than any other area of study, is its flexibility, its

adaptability, and the scope of its usefulness.

How's that? Well, as many articles below point out, while there might not be a single, obvious career path associated with philosophy, this by no means indicates that there aren't any at all. Rather, there is no *one* clear way to go with a philosophy degree because there are *so many* ways to go. The very misleading appearance that philosophy isn't useful for a career is largely a function of the fact that there is not just a *single* type of thing you can do having studied philosophy, no well beaten path to one or two specific jobs. Rather, the analytic writing, problem solving, and critical reasoning abilities that are honed razor sharp doing philosophy are essential to an enormous range of careers, and are useful and valuable in virtually any context and for all kinds of 'gigs'. As lots of these articles also point out, employers from all over the spectrum have already come to appreciate this fact - and those that haven't are quickly getting on board. So, when someone asks you that question: "Philosophy - what are you going to do with that?" there's actually a lot to say in response!

By the way, I also remember well that it can be difficult to justify picking up a philosophy major (or minor) to practical minded parents who are unfamiliar with the subject. This can be especially if true if those parents are helping foot the college bill, and have trouble seeing philosophy's worth or do not yet understand its genuine concrete benefits. Some of the links here talk about philosophy and its practical virtues in a way that can help alleviate these kinds of concerns and reassure worried parents. - DRK

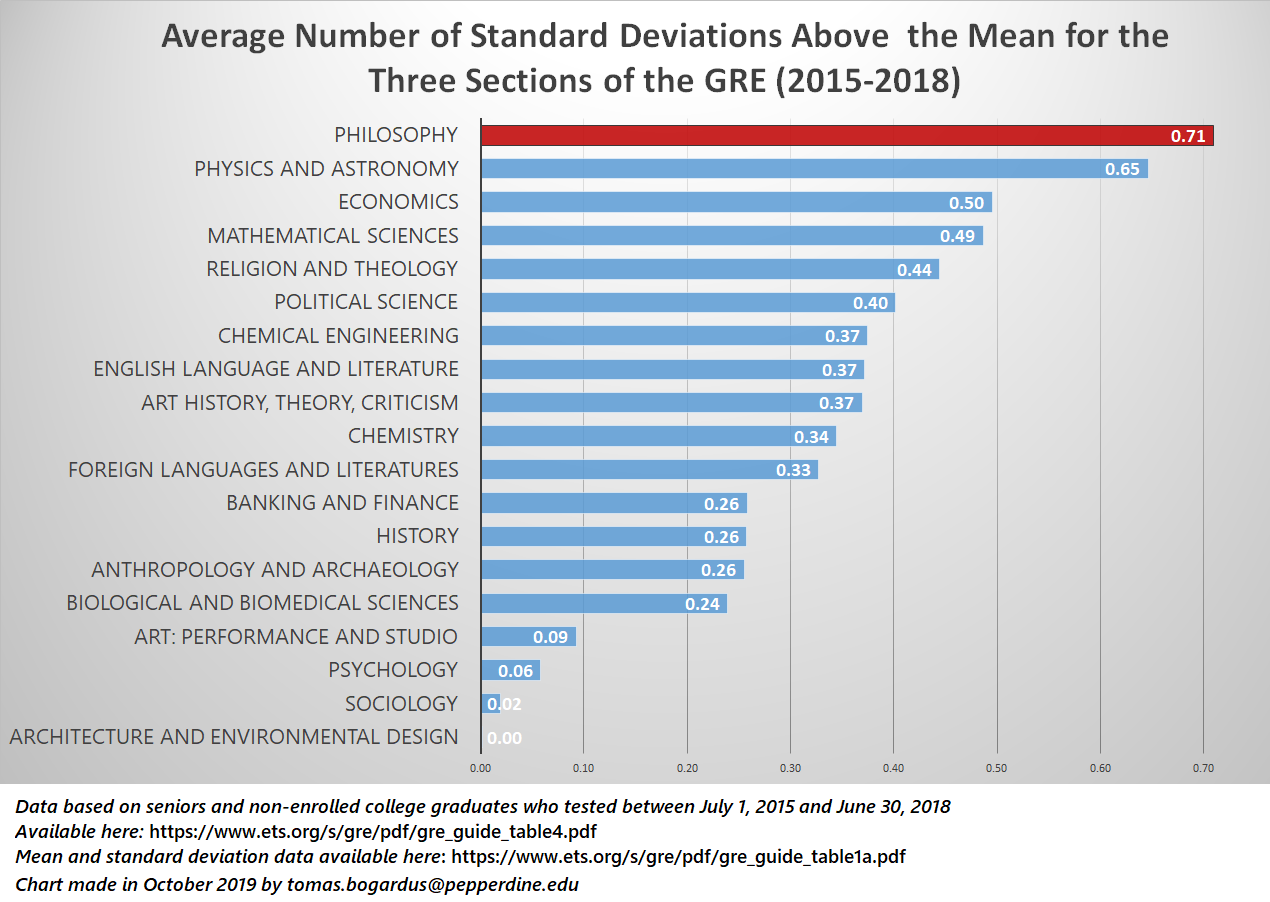

• Check out Purdue College of Liberal Arts Degree+ program, which is excellent. It's basically an administrative hack that allows you to pick up a secondary major in philosophy to go with your primary major, and not have to satsify any other College of Liberal Arts requirements (like, for instance, the language requirement.) This makes it significantly easier to do two majors where each major is housed in a different college. And so easier to get yourself some of that sweet, sweet high test score action! (For a fuller discussion of the graph about test scores on the top of this page, see here.

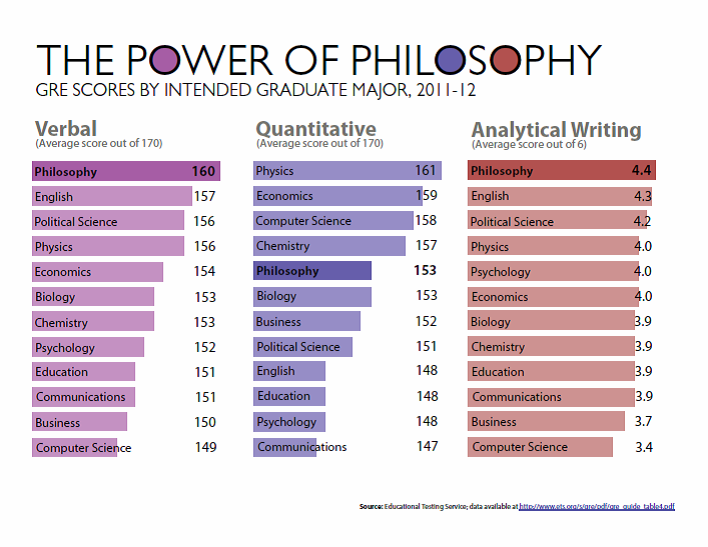

• Best Majors for GRE Scores? Philosophy dominates. Philosophy majors have a well established record of strong showing: 2016, 2014, 2013, and 2012; check out the graph below this bulletpoint (and discussed in more detail here) that breaks the 2012 numbers down by Verbal/Quantitative/Analytic Writing. Also note that this is just the most recent instance of a long standing trend of correlation between majoring in philosophy and performing well on a range of important standardized tests, including the GRE, GMAT and LSAT.

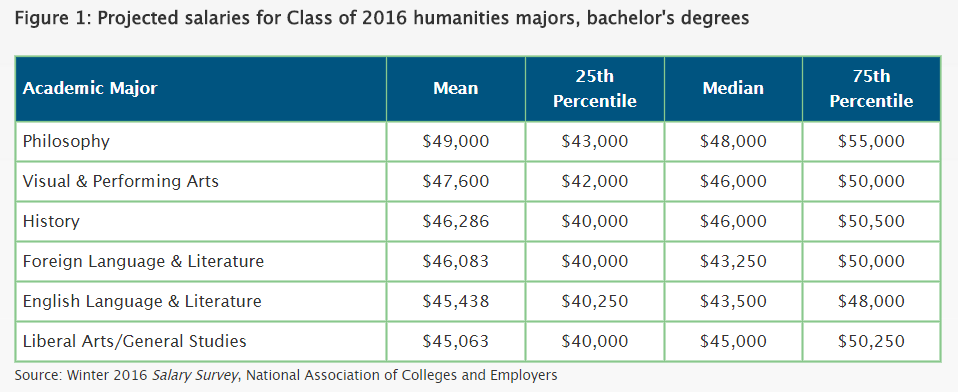

• The National Association of Colleges and Employers projects that philosophy majors are projected to be the top-paid Class of 2016 humanities graduates at the bachelor's degree level:

• Those with philosophy degrees were ranked dead last in one important job related category: unemployment. Of the 34 different kinds of majors compared in this recent report, philosophy majors came in 34th with only a 5% unemployment rate. Put in more positive terms: in this study, those with a philosophy degree were more likely to have a job than those with any other degree.

• The upshot of the previous bulletpoint about employability is a not a coincidence - with automationpositioned to bring with it enormous shifts in the economy and the kinds of skills required by employers, philosophy is well positioned to provide you with the kind of flexible and widely applicable intellectual proficiencies that will be needed in an increasingly large variety of professions and careers. In a recent article in Time Magazine, tech entrepreneur and billionaire Mark Cuban agreed: "So a new skill will become more in-demand than it ever has been creative thinking "I personally think there's going to be a greater demand in 10 years for liberal arts majors than there were for programming majors and maybe even engineering," he said. "When the data is all being spit out for you for you, options are being spit out for you, you need a different perspective in order to have a different view of the data." In particular, experts in philosophy or foreign languages will ultimately command the most interest from employers in the next decade, Cuban said."

• The Wall Street Journal on why, now more than ever, the world needs philosophy and big ideas.

• A good article and accompanying video addressing the question What does philosophy actually do? and discussing why it's worth studying that hits some good notes: "the study of philosophy cultivates a healthy scepticism ... teaches one to detect ‘higher forms of nonsense’, to identify humbug, to weed out hypocrisy, and to spot invalid reasoning ... teaches us to raise questions about questions, to probe for their tacit assumptions and presuppositions, and to challenge these when warranted. In this way it gives us a distance from passion-provoking issues – a degree of detachment that is conducive to reason and reasonableness."

• A recent article in The Atlantic about the future earning power of students who have an BA in philosophy, which is probably much greater than you might expect. From the article: ""We hear again and again that employers value creative problem solving and the ability to deal with ambiguity in their new hires, and I can't think of another major that would better prepare you with those skills than the study of philosophy. ... Experts say that while philosophy majors might not come out of college with the skill-set that business majors have, they have creative problem solving abilities that sets them apart."

• Yahoo Finance also reports that by mid career a person with a philosophy degree is likely to earn more than a person with an accounting degree, and that philosophy degrees also have the highest earning power of the humanities. Philosophy recently came in 49th of the 207 ranked majors.

• An informative article that discusses what past philosophy majors from Purdue have gone on to do with their degrees, as well as some other benefits of studying philosophy, published in Purdue CLA's THINK Magazine.

• An article in the The Washington Post arguing Why kids — now more than ever — need to learn philosophy.

• An article in the Harvard Business Review explaining How Philosophy Makes You A Better Leader.

• In a similar vein, this Slate article Be employable, study philosophy lays out how "The discipline teaches you how to think clearly, a gift that can be applied to just about any line of work".

• An article in which people in the military explain Why Air Force Cadets Ought to Study Philosophy.

• A very nicely done poster of famous people who were philosophy majors or minors put together by Catherine Nolan, a philosophy graduate student at SUNY Buffalo.

• Famous philosophy majors and the wide variety of careers at which they've succeeded, including 9 famous business executives.

• An article in The Huffington Post about the unexpected way philosophy majors are changing the world of business.

• A short article in The Denver Post arguing that philosophy prepares you for a variety of different career paths.

• A short article in The Atlantic arguing that philosophy might be, surprisingly, the most practical major.

• Want a successful career in technology? Study philosophy, recommends google's Damon Horowitz.

• Best Undergrad College Degrees By Salary (circa 2008); not too shabby.

• Philosophy is Back in Business, an article singing the praises of a philosophy degree published in Business Week, of all places.

• An article in Harper's, written by the founder of a consulting firm, arguing that if you want to succeed (even in business), don't get an M.B.A., rather study philosophy.

• An article in The Guardian, entitled "I think, therefore I earn" with some answers to the question, "A philosophy major? What are you gonna do with that?".

• Get information on Purdue's course requirements for a major or minor degree in philosophy here.

• Get information on the Purdue Undergraduate Philosophy Society here and here.