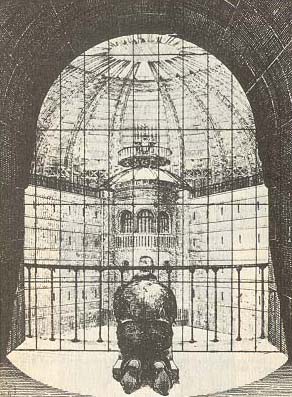

We began with some of 1984's direct influences

on popular culture (X-Files ["Talitha Cumi" episode], TNG [Picard tortured

by a Cardassion], etc.) and even on social theory (through Foucault). I illustrated

certain direct similarities between sections of 1984 and Foucault's

Diclipline and Punish: "There was of course no way of knowing whether

you were being watched at any given moment" (Orwell 6); "the inmate must never

know whether he is being looked at at any one moment; but he must be sure

that he may always be so" (Foucault 201); "[E]ven [a momentary contact] was

a memorable event in the locked loneliness in which one had to live" (Orwell

19); "They are like so many cages, so many small theatres, in which each actor

is alone, perfectly individualized and constantly visible" (Foucault 200);

"The crowd, a compact mass, a locus of multiple exchanges, individualities

merging together, a collective effect, is abolished and replaced by a collection

of separated individualities" (Foucault 201).

We began with some of 1984's direct influences

on popular culture (X-Files ["Talitha Cumi" episode], TNG [Picard tortured

by a Cardassion], etc.) and even on social theory (through Foucault). I illustrated

certain direct similarities between sections of 1984 and Foucault's

Diclipline and Punish: "There was of course no way of knowing whether

you were being watched at any given moment" (Orwell 6); "the inmate must never

know whether he is being looked at at any one moment; but he must be sure

that he may always be so" (Foucault 201); "[E]ven [a momentary contact] was

a memorable event in the locked loneliness in which one had to live" (Orwell

19); "They are like so many cages, so many small theatres, in which each actor

is alone, perfectly individualized and constantly visible" (Foucault 200);

"The crowd, a compact mass, a locus of multiple exchanges, individualities

merging together, a collective effect, is abolished and replaced by a collection

of separated individualities" (Foucault 201).

We then discussed how Foucault's later work tempers some of the tendencies of his earlier Discipline and Punish. As was pointed out, one potential problem of the earlier work is that, like contemporary conspiracy-theory narratives, it tended to represent Power as some abstract entity "out there," hence as something that one cannot even correctly pinpoint, let alone combat. The later work makes clear that power never exists on its own but refers to the relations that we have to each other. As a result, "Power is exercised only over free subjects, and only insofar as they are free...; slavery is not a power relationship when man is in chains. (In this case it is a question of a physical relationship of constraint.)" (221). In other words, power is not per se a bad thing: in fact, it is the baseline for our freedom and mutual respect. The very act of saying "hello" entails an acknowledgment of an other's power over me on some level. Foucault's definition of power also suggests to what extent we are each responsible for the governments that we choose to allow to exist. (Adolf Eichmann was our heuristic example in Nazi Germany since he is so closely aligned with a character like Winston who, despite his rebellious spirit, continues to do his bureaucratic job well [see, for example, p. 91 and p. 151 of 1984].) Foucault's point throughout his writings is not that we live in a world like that of 1984 but that the potential for such a world is inherent in our own society (which is structured in much the same way as Nazi Germany). The slide into totalitarianism occurs the moment one refuses to accept one's responsibility to change what is unjust in one's own society.

This led to a fascinating discussion about the very nature of responsibility in postmodern societies, a discussion led by Emily Rosko, Graham Sadtler, Bess Mattern, Jonas Moskowitz, Dan Bender, Tim Phelan and Vanessa Leamer.

We then discussed the relation of 1984 to Foucault's theories and came to the conclusion that O'Brien's theories about power more closely resemble the earlier Foucault of Discipline and Punish: As O'Brien explains, "The Party seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power. Not wealth or luxury or long life or happiness; only power, pure power.... Power is not a means; it is an end.... The object of persecution is persecution. The object of torture is torture. The object of power is power" (217). In other words, Orwell is pointing out that systems of power in a bureaucratic state tend to persist for the sake of the system. As Max Weber will state in a reading we will get to next week, "Even in case of revolution by force or of occupation by an enemy, the bureaucratic machinery will normally continue to function just as it has for the previous legal government" (338). As Craig Stalbaum pointed out, the reason that the Party must be so closely monitored, unlike the proles, is that its members are the representatives of that bureaucracy, which seeks the perfection of the system, no matter how seemingly crazed the search for order and perfection might seem. As Orwell writes, "The new aristocracy was made up for the most part of bureaucrats, scientists, technicians, trade-union organizers, publicity experts, sociologists, teachers, journalists, and professional politicians" (169). It is made up, that is, of experts who become at once increasingly specialized (and thus separated from the others in the bureaucratic machine) and increasingly faceless ("I'm just doing my job"). We then discussed how this definition resembles and differs from Foucault's definition of power. Orwell and Foucault agree that "power is power over human beings" (Orwell 218) or, as Foucault states, power "is... always a way of acting upon an acting subject or acting subjects by virtue of their acting or being capable of action" (220). The difference is that O'Brien in Orwell's story claims that "The individual only has power in so far as he ceases to be an individual" (218) whereas Foucault in "The Subject and Power" states that "Power is exercised only over free subjects, and only insofar as they are free" (221).

BACK TO COURSE

SYLLABUS

BACK TO COURSE

SYLLABUS