A Library of Clouds

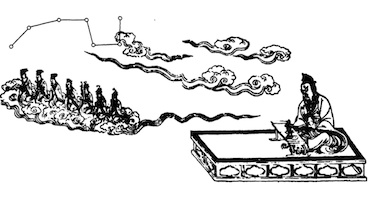

Studies of sacred texts tend to treat scripture as an immutable text, a writing (or perhaps an icon or symbol) that is readily recognizable to a community of readers. In the academic study of scriptures, such texts are often reified and treated as agents exercising force or influence in readers’ minds. Many studies incorporate notions borrowed from Christianity like “belief” and “truth” to characterize the processes in which people hear a text and choose to either adopt or reject its sacred message. Seeing scriptures as rigid entities, however, severely hampers our recognition of the complexity of Chinese sacred texts. In China, temple groups typically adhere to an “open canon” of scriptures, meaning that divinely inspired texts are continually revealed and added to previously existing ones. Thus for Chinese temples worldwide, scriptures tend to be quite fluid entities, continually made and re-made by way of revelatory experiences.

I am currently in the final stages of editing my first book, which is co-authored with Dr. Chang Chao-jan of Fu-jen University. Titled A Library of Clouds: A Bibliographic History of Early Daoist Scriptures, this book explores the production and circulation of early Daoist manuscripts. Our analysis focuses on texts that have hitherto been disparaged as redactional forgeries, fabrications, or falsifications. We argue that these texts, which were continually erased, augmented, and rewritten, help us rethink what reading Daoist scriptures might have meant in medieval China. Whereas previous studies of Daoist scriptures tend to treat these texts as authoritative and fixed entities, we argue that they were malleable media that allowed for considerable reinterpretation and expression. We conclude that “reading” and “writing” overlapped a great deal in medieval China, as readers actively reinterpreted texts, rather than passively receiving them.